Macroeconomic environment and market sentiment

Table of contents / search

Table of contents

Executive summary

Introduction

Macroeconomic environment and market sentiment

Asset side

Liabilities: funding and liquidity

Capital and risk-weighted assets

Profitability

Operational risks and resilience

Special topic – Artificial intelligence

Retail risk indicators

Policy conclusions and suggested measures

Annex: Sample of banks

List of figures

List of Boxes

Abbreviations and acronyms

Search

The macroeconomic landscape shows signs of improvement, though uncertainties and tail risks remain

In the beginning of 2024, the macroeconomic environment in Europe showed signs of improvement with a gradual increase in economic activity and central banks successfully tempering inflation. Nevertheless, the region remains vulnerable to potential downturns in global economy due to escalating uncertainties stemming from geopolitical tensions, concerns about economic growth in the US and downside risks from property sector adjustments in the Chinese economy. These factors might not only disrupt supply chains but could also impede global trade developments and have overarching impacts on EU/EEA banks (see Box 1).

Economic activity in the EU has gradually rebounded after subdued levels in 2023. During the first half of 2024, activity showed slight improvement, but growth rates of 0.3% in Q1 and 0.2% in Q2[1] (Figure 1) remained slow. Economic growth, however, is not uniform across European Member States. Indeed, some countries are experiencing minimal growth, while a few even recorded slightly negative growth rates.

Source: Eurostat

Following a substantial tightening of monetary policies by central banks across Europe, inflation pressures have significantly eased, from the average inflation rate of 6.4% in 2023. For example, in the first half of the year, the EU saw an average inflation rate of 2.6%. Although inflation rates are still above target levels in many jurisdictions, the ECB has already implemented three interest rate reductions, in June, September and October 2024, and several other central banks have also eased their monetary policies. Interest rates are a crucial tool for central banks to steer economic activity, affecting factors such as inflation, consumer spending, and overall economic growth. For banks, interest rates are key in determining their profitability, lending capacity, and financial health (see Chapters 2, 5 and 6). Although for several currencies interest rate market rates remain at elevated levels, the stabilisation of the interest rate environment provides a more predictable operating setting for both borrowers and banks (Figure 2).

Source: Eurostat

Sources: Refinitiv, Central Bank of Iceland, Central Bank of Romania

(*) EURIBOR (Euro Interbank Offered Rate), CIBOR (Copenhagen Interbank Offered Rate), BUBOR (Budapest Interbank Offered Rate), REIBOR (Reykjavík interbank offered rate), ROBOR (Romanian Interbank Offered Rate), STIBOR (Stockholm Interbank Offered Rate), WIBOR (Warsaw Interbank Offered Rate), NIBOR (Norwegian interbank offered rate).

The low unemployment rates have also provided a benign macroeconomic landscape for banks in the European Union. The EU’s unemployment rate has remained steady at 5.8% during the first half of the year and is anticipated to maintain this level, according to the EU Commission Spring Economic Forecast. In addition, even though wages and employment are increasing at a more gradual rate, they continue to enhance disposable income growth and revive consumer confidence while supporting banks’ asset quality (see Chapter 2.2).

Box 1: Geopolitical landscape increases risks for the banking sectorBanks within the EU/EEA have reported nearly EUR 5 tn[2] in exposures to counterparties located outside the EEA, which is 23.4% of their total exposures. Over the past year, these exposures increased significantly by more than EUR 350 bn (7.9%). A substantial portion of this growth was driven by increased exposures to counterparties based in the United States (EUR 1.3 tn in June 2024, an 11.8% YoY increase). The United States remains the largest non-EEA counterparty for the EU banking sector, followed by the United Kingdom (EUR 900 bn). Exposures to emerging markets also rose and equalled those of the UK. Geopolitical tensions have intensified globally over the past few years amid deteriorating diplomatic relations between the United States and China, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and war in the Middle East, and further conflicts around the globe. Although exposures to these regions are not negligible, they only account for a fraction of total exposures of the EU/EEA banking sector. Banks have almost EUR 225 bn in exposures to Middle Eastern countries, with Turkey and the UAE alone representing nearly EUR 100 bn and over EUR 45 bn, respectively. Exposures to nations directly affected by the conflict in the Middle East are limited to under EUR 10 bn, mostly towards Israeli counterparties (EUR 7 bn). Chinese counterparties account for about EUR 80 bn, while Taiwanese exposures are around EUR 18 bn. Exposures to entities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus are below EUR 45 bn. Threat from terrorism is also widely elevated level, and there are increasing risks of rising trade barriers and the introduction of new tariffs. Geopolitical risks can adversely affect both the financial markets and the real economy, as well as the linkages between the two, representing a threat to financial stability. On the financial side, an increase in geopolitical risks can lead to restrictions on capital flows and payments or increased investors’ risk aversion, thereby affecting cross-border capital allocation and asset prices. This can result in heightened volatility in financial markets. On the real economy side, an increase in geopolitical risks can lead to restrictions on the import/export of goods and services or disruptions to supply chains, thereby affecting international trade and economic growth, and generating inflationary pressures. The interconnections between the two channels can potentially give rise to a detrimental feedback loop between the real economy and the financial channel, thus amplifying the overall impact of geopolitical risk on financial stability[3]. Geopolitical risks may also amplify existing vulnerabilities leading to situations of severe distress. These risks may have a direct and indirect impact on the EU/EEA banking sector, as counterparties of EU/EEA banks are spread across over 220 countries and have exposures to sectors potentially vulnerable to geopolitical risks. The direct impact could result from heightened credit risk associated with exposures to counterparties located in countries experiencing increased geopolitical risk. Additionally, there may be indirect effects arising from supply chain disruptions caused by geopolitical tensions and reduced demand for European products due to imposed tariffs. The latter can be a result of political developments regarding trade policies, including tariffs, trade agreements and import/export regulations. Protectionist policies might affect international trade flows, corporate earnings and overall market sentiment. In broad, political uncertainty can create a risk-averse environment, leading to decreased investment and market activity, potentially prompting investors to seek ‘safer assets’, leading to capital flight and reduced market liquidity. Prolonged political instability can hamper economic growth, affecting not only corporate profits, but market performance too. Political uncertainty can manifest itself through governmental instability, for instance where frequent elections resulting from hung parliaments might lead to significant policy changes, or rising threat from so-called populist parties and / or politicians. These shifts can impact market expectations and investor-behavior. These factors could negatively influence the performance of the banking sector, affecting lending volumes and practices, risk management and capital requirements. They can also increase operational costs for banks, potentially reducing profitability. Market, liquidity, and operational risks can also be impacted, for instance, during financial market turmoil, increasing margin call demands, and interconnectedness between banks and sovereigns. Potential impacts may also involve employers, offices, branches, and systems being affected by an escalating conflict or terrorist attack. Other associated risks encompass increasing ICT and cyber[4] threats, which may involve potential complications with third-party providers, for example. The emergence of geopolitical risks can lead banks to face increasing legal and AML risks, alongside dealing with fresh sanctions and related measures that increase operational risks. These challenges also extend to correspondent banking and impact internal frameworks and processes such as prudential and accounting models, as well as valuation procedures. Banks must be adequately prepared to manage these risks. EU/EEA banks show notable exposure to some vulnerable geopolitical risks sectors, but only limited direct exposures to vulnerable countriesThe following analysis primarily addresses the aspect of credit risk, evaluating vulnerability via direct as well as – to the degree possible – certain indirect effects. An essential phase of this assessment involved identifying countries and the business sectors potentially most susceptible to geopolitical risk. The identification of the most vulnerable countries was based on country risk scores[5]. In concrete, S&P Capital IQ’s country risk scores were used. The score considers political, economic, legal, tax, operational and security risks that arise from doing business with or in a specific country. The scale ranges from '1' (very low risk) to '10' (extreme risk). For the purpose of the analysis, all countries classified at least as ’high risk’, i.e. those with an overall country risk score of 2.4 or above, were considered. This resulted in the selection of 82 countries, of which 10 were identified as severe-risk countries with an overall risk indicator of at least 4.4. EU/EEA banks’ direct exposures to these geopolitically high-risk countries exceeded EUR 500 bn as of June 2024, representing around 2.5% of the total exposures of EU/EEA banks. A significant concentration of these exposures was found in Spanish banks through their subsidiary operations in Mexico and Turkey (around EUR 220 bn and EUR 57 bn), though notable exposures to higher geopolitical risk countries are present throughout several banks in Europe, albeit with a great degree of heterogeneity. In most EU/EEA countries, banks reported direct exposure to countries vulnerable to geopolitical risks of less than 4% of their total exposures. While countries such as Spain, Hungary and Croatia have slightly more such significant exposures, it was nevertheless less than 11% of their total exposures (Figure 3). The identification of the most vulnerable business sectors was based on the simple correlation between the equity performance of relevant sectors, as indicated by selected Euro Stoxx sectoral equity indices, and the GPR Daily Index, considering a time horizon of 3 years, from mid-September 2021 to mid-September 2024[6]. For the analysis, the five sectors that exhibited the highest negative correlation with the GPR Index were selected and assumed to be those facing particularly elevated vulnerabilities relating to rising geopolitical risks. The findings of the analysis showed that businesses related to accommodation and food service activities, transport and storage, information and communication, trade, and manufacturing were the most negatively correlated. Businesses concerning human health services and social work activities as well as construction showed an intermediate correlation. On average, the proportion of banks’ exposures to business sectors susceptible to geopolitical risks was around 40% of total NFC loans for EU/EEA banks, with notable variability. For several jurisdictions, more than half of total loans to NFCs concerned businesses operating in vulnerable sectors. This percentage increased further exceeding 60% for Greece, Slovenia, Cyprus and Bulgaria (Figure 3). Sources: Caldare and Iacoviello, Refinitiv Workspace, S&P Capital IQ, EBA supervisory data and calculations |

The average debt-to-GDP ratio of European Union was reported at 82% in early 2024, representing a year-over-year decrease of 1%. There are, however, material country-level variations. Although interest rates stopped increasing and debt-to-GDP ratios slightly declined, sovereign bond yields slightly increased in the first half of 2024. This rise was not least driven by continued uncertainty regarding the future path of interest rates, as well as reflecting prevailing market concerns and potential risks to geopolitical stability. Elevated interest rates and sluggish economic growth have highlighted concerns about sovereign debt levels and their sustainability, underscoring the potential risks of intensifying the sovereign-bank nexus. Risks are key for financial stability, given the considerable exposure of EU/EEA banks to sovereign debt (see Chapter 2.1) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Debt-to-GDP levels for European countries (top), Yields of selected European 10-year sovereign bonds (bottom) (%)

Source: Eurostat

Source: Refinitiv

Despite outperforming other sectors, European bank stocks remain susceptible to market volatility

European market performance remained closely linked to global economic changes and policy shifts. Markets acted sensitively to central bank actions, fiscal policies and geopolitical factors that influenced their performance in 2024. Yet, equity markets demonstrated resilience during 2024 also due to strong corporate earnings. European banking sector stocks, in particular outperformed most of the other indices, benefiting from the interest rate environment and solid profitability of the sector (see Chapter 5). Markets, however, have been especially volatile during 2024, facing pronounced upheavals. These disruptions were unrelated and caused by external factors such as France’s political instability in June (i.e. snap elections) or the rate hike in Japan which was coupled with poor performance of US job markets that spurred fears of a recession in late summer (see Box 2). Even though these disruptions were brief, high macroeconomic uncertainty and increasing ties between banking and NBFIs (see Box 3) suggest potential future vulnerabilities to sudden incidents (Figure 5).

Source: Refinitiv

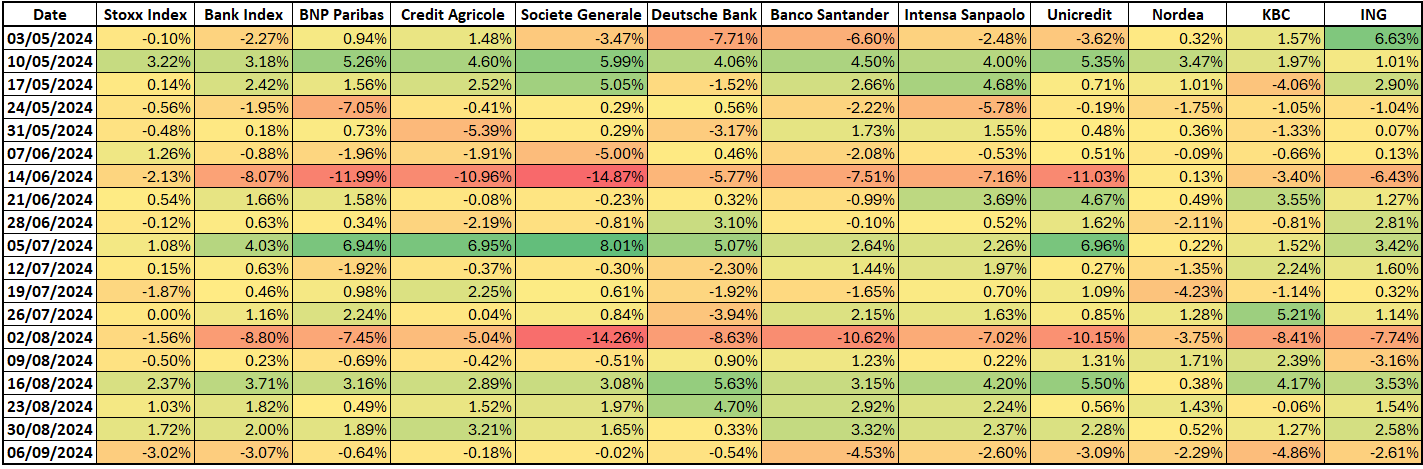

Box 2: Rising market volatility affects banksBanks depend on a stable economy to function effectively. High volatility, caused by economic instability, political uncertainties, or monetary policy changes, leads to greater risks in lending and investments. This unpredictability can increase loan defaults and reduce asset values, harming banks’ balance sheets. Banks maintain a diverse portfolio of assets such as loans, mortgages, and various securities. The latter are highly responsive to market dynamics. In times of market turbulence, their values can experience marked volatility, potentially resulting in substantial losses. An abrupt hike in interest rates can diminish the value of bonds and other fixed-income instruments in banks’ holdings, thereby impacting their profitability. Increased market volatility can also hinder banks’ liquidity positions and increases the liquidity risk (see Chapter 3.3). Investor confidence plays a pivotal role in the banking industry. Turbulent market conditions can undermine this confidence, potentially triggering a sell-off in banking equities. High levels of perceived uncertainty and risk prompt investors to shift their funds towards safer assets such as government bonds or gold. This flight to safety often leads to a drop in bank stock prices, complicating efforts for banks to raise capital via equity markets. The VIX measures the implied volatility and indicates the markets’ expectations of volatility over the next 30 days. This index is famous for reflecting investors sentiment and market uncertainty. Usually there is an inverse correlation between the index and the stock market movements, i.e. when the VIX surges the stock prices drop. The index has been mostly below 15 since the beginning of the year with the exception of a short-lived spike in March. However, since June, market volatility has increased significantly peaking at 38.6 following the ‘Carry Trade Event’[7]. After this event, volatility levels remained elevated in comparison to the rest of 2024. Multiple factors may have contributed to this market volatility. The initial spark might have been Japan’s central bank deciding to raise its policy rate, triggering the carry trade unwind, but market participants were also concerned about various economic data from major economies that fell below expectations. This included slow growth in China and concerns over a possible recession in the United States. Moreover, central banks, particularly the Federal Reserve, hinted at potential interest rate hikes to combat inflation, raising concerns among those worried about the impacts on economic growth. Additionally, geopolitical tensions and a series of disappointing earnings reports from corporations further exacerbated market uncertainty and added to the negative sentiment. (Figure 6). Source: Bloomberg These market volatility spikes also impacted banks’ stock prices. In fact, European bank shares saw more pronounced price corrections, significantly underperforming the General European Index [8] during the summer market downturns. While the June corrections in banking equities, was more evident for French banks, due to country’s political uncertainty, the price corrections were more widespread during the August market turmoil (the bank index suffered losses of 8.3% over 2 trading days, whereas the general Eurostoxx index declined by only 3%). This was likely because the recent market turmoil was closely tied to developments in interest rates (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Sources: Refinitiv, Bloomberg (*) Eurostoxx (SXXE) Index and Euro Stoxx Bank (SX7E) Index which are part of the Eurostoxx Index, to secure comparable results. Eurostoxx Banks (SX7E) Index is a capitalisation-weighted index which includes listed banks in countries that are participating in the EMU. Figure 8: Selected European Banks Weekly changes of stock prices (%) * (*) The banks’ sample covers different European jurisdictions but with a heavier weight towards French banks, following the political events in France. As price reference closing price of the last trade (TRDPRC_1) was used for Refinitiv data. While volatility can create trading opportunities, it generally presents considerable difficulties for banking stocks. Fluctuating markets can reduce asset values, erode investor confidence and adversely affect profitability. Consequently, stability and predictability are crucial in the banking sector, making volatility unfavourable. Considering the episodes of heightened market volatility in 2024 and the ongoing macroeconomic uncertainty, increased caution is advised. Potential escalations in market volatility may arise from various sources, such as geopolitical tensions, political developments, and macroeconomic factors, including fiscal policy decisions and subsequent central bank monetary policies. |

Real estate markets are stabilising, but conditions could deteriorate once more

After the 2023 slump in CRE prices, the first half of 2024 has shown price stabilisation. Although transaction activity remains low, CRE prices were estimated around 35% below their peak. Nevertheless, market sentiment has improved marginally over the course of 2024. Likewise, RRE prices appear to be stabilising too, suggesting a positive outlook for the market. House prices have increased by 1.3% YoY in the EU, while the euro area has seen a decrease of 0.4%. With inflation easing and cuts in interest rates, demand for loans in most main sectors has increased for the first time since 2022 (+2.1% YoY in September 2024) and is expected to rise further, according to the ECB lending survey[9]. There are, however, significant discrepancies between regions. In general, the drop in RRE prices has been more pronounced in countries that experienced higher property overvaluation at the onset of the rate hike cycle. Given the considerable exposure of EU/EEA banks to real estate, the stabilisation of these markets creates a favourable setting, enhancing both asset quality and profitability prospects (see Chapters 2 and 5).

Source: Eurostat

Source: ECB

|

Abbreviations and acronyms

[1] EU Commissions’ spring 2024 forecasts suggests that GDP growth will reach approximately 1% in 2024 and 1.6% in 2025 (0.8% and 1.4% for euroarea respectively). Spring 2024 Economic Forecast: A gradual expansion amid high geopolitical risks

[2] Exposures includes debt securities and loans and advances

[3] See also “Turbulent times: geopolitical risk and its impact on euro area financial stability” in the ECB’s Financial Stability review, May 2024.

[4] According to the Financial Stability Board (FSB), cyber risk is defined as the combination of the probability of cyber incidents occurring and their impact.

[5] S&P Capital IQ’s definitions for country risks scores.

[6] The analysis involved the use of selected Stoxx Europe sectoral equity indices that were considered to be illustrative for profitability trends in the business sectors, classified according to NACE Rev. 2 sections, to which EU/EEA banks have exposures. It was not possible with the GPR Index to assess the correlation of all sectors to which banks have exposures, due to the lack of sufficiently representative or well capitalised indices. Moreover, it should be noted that even the selected indices are subject to idiosyncratic risks, which precludes their consideration as fully representative.

For the purpose of this analysis, the recent “GPR daily Index” was also used. Dario Caldara and Matteo Iacoviello developed measures of adverse geopolitical risks based on a tally of newspaper articles covering geopolitical tensions. The indices have been employed in a multitude of analyses pertaining to geopolitical risks and have been referenced in a substantial number of institutional publications, including by the ECB, the IMF, and the OECD. For further information see Caldara, Dario and Matteo Iacoviello (2022), “Measuring Geopolitical Risk,” American Economic Review, April, 112(4), pp.1194-1225, and the Geopolitical Risk (GPR) Index. Furthermore, the selection of the temporal scope was intended to minimise the influence of the pandemic on the sectors of interest, allowing for a more accurate analysis.

[7] Carry Trade is a trading strategy which involves borrowing at a low interest rate and reinvesting in a currency or investment with higher return. For the specific event, the market participants borrow Yen – due to the low-interest rate environment in Japan and fund investments in assets elsewhere that offer higher returns. However, on 31st July 2024 the Bank of Japan raised its key interest rate which triggered investors to unwind their carry trades.

[8] The Euro Stoxx Index is a broad yet liquid subset of the Stoxx Europe 600 Index. The index represents large, mid and small capitalisation companies.

[11] Based on bank-level data from FINREP supervisory reporting; this data provides a granular breakdown by financial instruments, however, it treats NBFIs as an aggregated sector that includes insurance corporations, pension funds, other financial intermediaries and investment firms. More detailed breakdowns in terms of counterparty sectors can be obtained from alternative data sources, however the coverage in terms of instruments and number of banks would be lower. Large banks are banks with total assets exceeding EUR 100 bn; medium-sized banks are banks with total assets between EUR 50-100 bn; and all other banks are classified as small banks. This box provides an in-depth discussion of banks’ asset-side exposures to NBFIs. For further insights into NBFI funding for EU/EEA banks (i.e. the liability side), see the EBA Risk Assessment Report published in July 2024.

[12] Although there is no universal definition of other financial intermediaries, according to the European System of Accounts (2010), this sub-sector includes, for example, financial leasing, hire purchase, personal and commercial financing, factoring, venture and development capital companies and import/export financing companies.